One of the more positive trends of the past few years has been the acknowledgement by at least some New York politicians, staring with Mayor Bloomberg and including Governor Cuomo and those in some cities upstate, that new businesses and new types of businesses are important. And that economic development involves acts of creation, rather than just being an excuse for the government to redistribute wealth to powerful existing interests through tax beaks and subsidies. A lesson not yet learned in New Jersey and Connecticut. At the same time, there has been a surge of new businesses in the Bay Area of California, and a cultural interest in early stage companies as a result of TV shows such as Shark Tank.

While there has been increasing interest in entrepreneurship, however, there is some evidence that there has been decreasing entrepreneurship. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal

http://www.wsj.com/articles/why-corporate-america-needs-competitive-spirit-1436384494

Across the country, the rate of new-business formations has been trending down for decades. According to Census data, the number of new firms in 2012 was equal to just 8% of the total, slightly below the number that closed. While that “entry rate” was up from the 2010 trough, it remains well below the levels that prevailed until the recession hit in 2007.

We are heading, the article’s author fears, toward an oligopolistic economy with less creativity, less investment, a less good deal for consumers and lower returns for investors, as a business/political elite seeks wealth not by starting small businesses and growing them into large ones, but seizing control of large existing organizations and pillaging them. Is this true, and how do New York and New Jersey compare? Let’s look at some data.

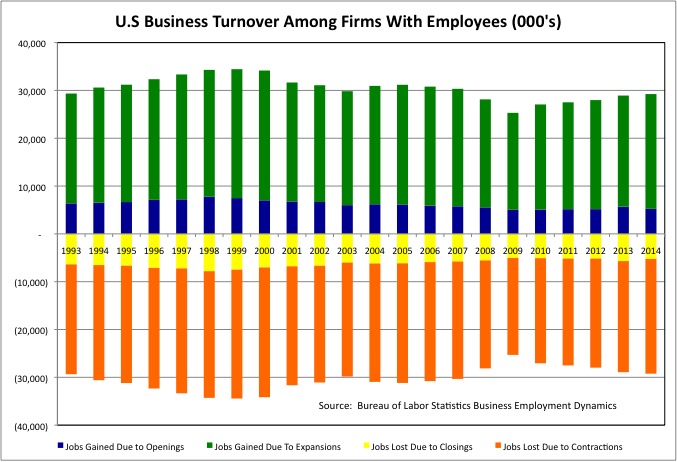

First, a brief overview of the information available. The usual economic and employment data is presented as an overall level, but this disguises the high level of turnover in the private sector economy. Total U.S. employment may go up or down by a few million jobs each year, at most, but the actual number of jobs created due to businesses opening and expanding – and closing due to businesses contracting and closing – is much greater – more than 30 million per year.

This chart makes expansions and contractions seem more important, and openings and closing less important, than they actually are, because an establishment is only considered “new” only in its initial quarter of having employment. Jobs gained in subsequent quarters as the business staffs up are considered “expansions.”

The analysis of business turnover was pioneered by David Birch around 1980, using business records data from Dunn and Bradsheet, and was later carried out by the Small Business Administration.

https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/an%20analysis%20of%20small%20business%20and%20jobs(1).pdf

After disappearing for a while, the analysis of business turnover has returned with the “big data” era, although it still doesn’t seem to get reported on in the mainstream media very much. The data referred to the Wall Street Journal article is here…

http://www.census.gov/ces/dataproducts/bds/data_firm.html

But I decided to take a look at the Business Employment Dynamics data, based on unemployment insurance records, provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

http://www.bls.gov/bdm/

Most of the data I used is in this spreadsheet.

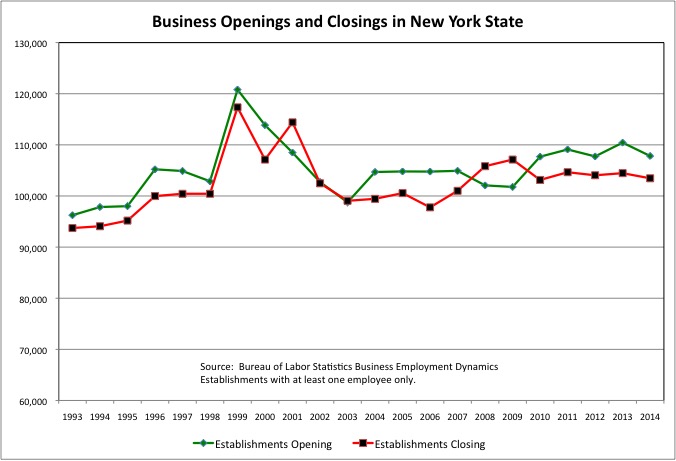

There certainly seems to be a booming business renaissance here in Brooklyn – and a growing interest in new firms Upstate now that the almost all the old industrial dinosaurs are finally gone (having taken decades of public subsidies with them). And the data in fact shows that in fact the number of new business establishments with is higher than it once was employees in New York State.

There can be too much of a new thing. Around the year 2000 too many people were starting, and financing, businesses that had no idea of how to get revenues and no chance of success. And while the arts are certainly a vibrant part of the NYC economy, sometimes I worry we may now have more art and live entertainment in this city than the people can support. Although it is certainly more fulfilling to spend what money you have on that, rather than on housing with more square footage or motor vehicles with more weight and lower miles per gallon.

A more moderate upturn in new businesses, however, is good news. And the bubble around 2000 aside, that is what we have in NY State. From 2010 to 2015 New York State averaged 108,550 new establishments with employees per year, up from 103,600 from 2003 to 2007 and from 101,800 from 1993 to 2007.

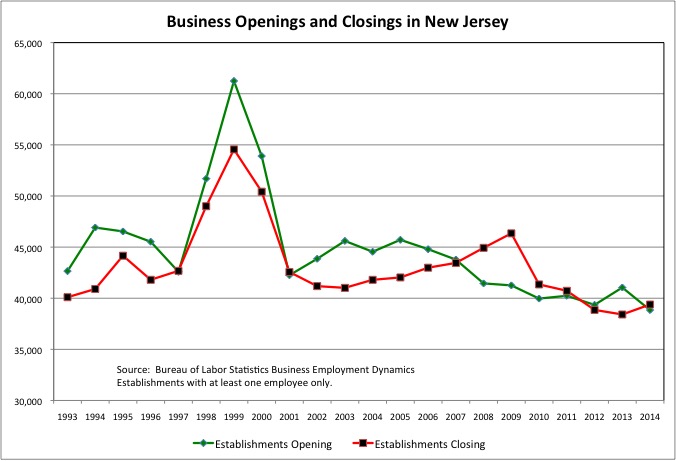

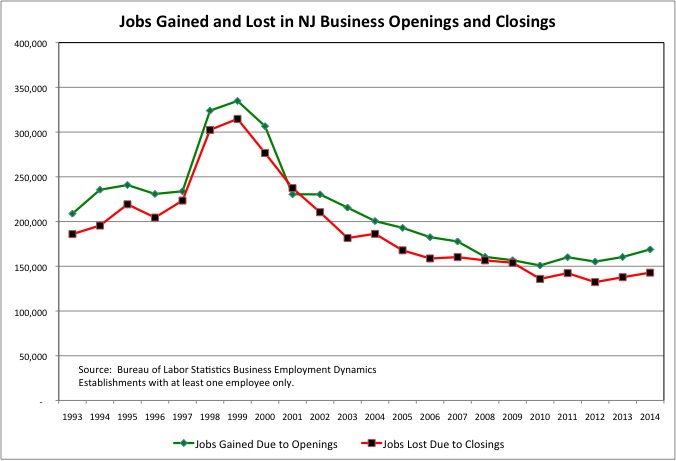

In New Jersey, on the other hand, the number of new business establishments with employees is down to around 40,000 per year, from around 45,000 per year before the Great Recession. A look at employment, however, shows something different.

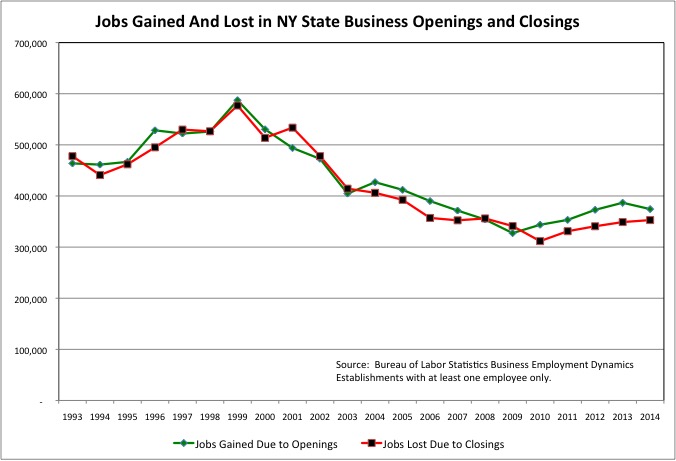

In New York State, the number of jobs gained by new establishments opening, over 400,000 each year from 1993 to 2005, has been below 400,000 each year since. For example in 1993, before New York City’s renaissance really got rolling, New York State gained 463,775 jobs due to new business openings, compared with just 374,300 jobs in new establishments in 2014.

Perhaps offsetting this downturn, however, there is simply much less work available these days that qualifies as a “job” and shows up in this data, and much more freelance, contract and internship work instead. As I noted in this post

https://larrylittlefield.wordpress.com/2015/08/02/it-keeps-getting-tougher-for-new-yorks-young-serfs/

The self-employed now account for about one-third of those working in Brooklyn and Queens. If you have four partners, six contract workers and an intern working for a start-up, they wouldn’t be counted in this data at all. In one of the more stunning trends of the past 15 years, in 2013 there were 1.14 million self-employed workers working in New York City, based on having filled out Schedule C for the federal income tax. This according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. That was double the number in the year 2000 and four times the low back in 1976.

Over in New Jersey, the number of jobs gained in new business openings has also trended down, from over 200,000 per year through the mid-2000s to just over 150,000 per year today.

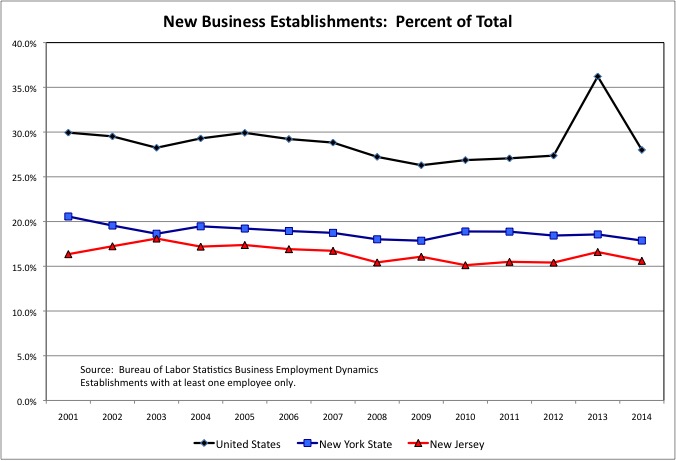

Starting in the year 2001, comparable data is readily available on the number of private sector establishments and jobs in total, allowing a tabulation of new establishments and their employment as a percentage of the total.

The data shows that establishments opening in a give year have always been a lower share of total business establishments in New York State compared with the U.S. as a whole, and in New Jersey compared with New York. In 2014, new establishments (that year) accounted for 28.0% of all private establishments with employees in the U.S., 17.9% in New York State, and 15.6% in New Jersey. There doesn’t seem to be much of a trend, other than a slight downward trend.

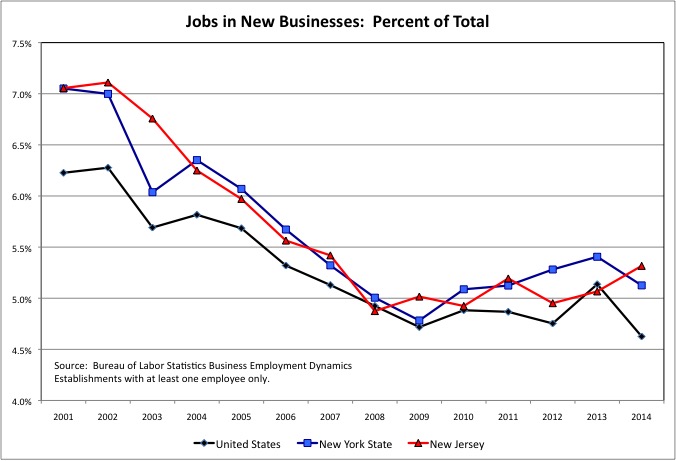

The data on the share of total private sector jobs in new businesses, on the other hand, shows a definite downward trend the U.S., New York State and New Jersey. Whether this is true because new businesses are less prosperous, or because they are less likely to have their workers be employees (rather than self-employed), is uncertain.

One thing that is certain is that in the wake of the Great Recession, certain parts of the U.S. – the Northeast, the West Coast, Texas – have been much more economically dynamic than the rest of the country. And the percentage of jobs in new establishments has been lower for the U.S. than for New York and New Jersey for some time. As of 2014, establishments new that year accounted for 4.6% of U.S. private sector jobs, 5.1% of New York State private sector jobs, and 5.3% of New Jersey private sector jobs.

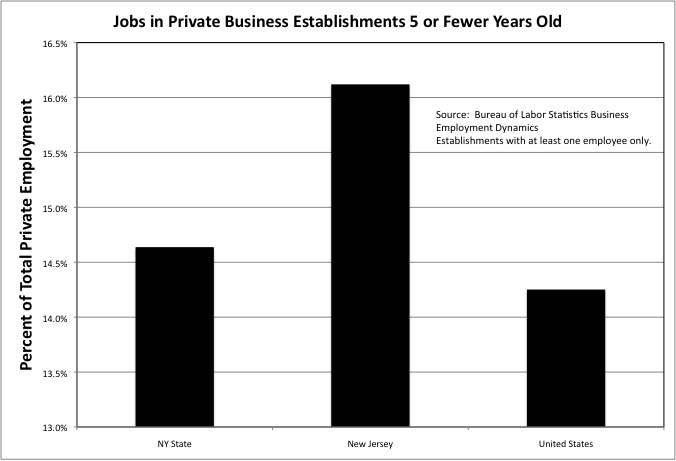

Most of those new establishments, however, don’t make it to their fifth birthday. New Jersey, which prospered by attracting big companies out of New York City for decades, is now going through its own restructuring even if its politicians don’t understand it. Business establishments that are five or fewer years old accounted for 16.1% of the private sector jobs in New Jersey in 2014, compared with 14.6% in New York State and 14.3% in the U.S. as a whole.

What about large existing firms? According to the Wall Street Journal, they are merging rather than creating and investing.

Profits are at or near all-time highs, both as a share of economic output or relative to assets. And the cost to borrow has seldom been lower. In a perfectly competitive world, firms ought to exploit those cheap borrowing costs to add profitable new capacity and products, until all the added competition pushes profits down.

That’s not happening, at least not yet. While capital spending has steadily risen from its recessionary trough, it remains—at 114% of cash flow—well below prior peaks of 142% in early 2008 and 157% in 2000.

The result is control of the market by a few large firms, which have the potential to provide a worse deal to consumers. Large existing companies, however, have become an increasing ripoff for investors was well. As noted by Marketwatch.com:

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/what-you-can-do-about-obscenely-high-executive-pay-2015-07-16

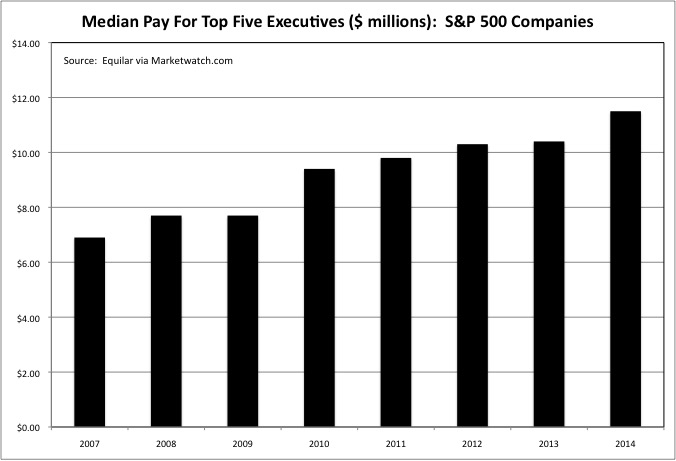

Companies have been going deeper and deeper into debt, not to invest in new plant, equipment or intellectual property, but just to buy back stock, temporarily inflating the stock price and with it executive pay. The stock buybacks are used to offset stock issued to top executives, sending their pay packages soaring.

What have U.S. top executives done to deserve this, other than wreck the economy to the extent that the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates at zero for nearly seven years? One saw on Friday, with its 500 point collapse for the Down Jones Industrial Average, what the mere possibility of a ¼ percent interest rate does to those stock prices, despite executive “genius.”

Companies haven’t invested because the false economy of paying Americans less yet selling them more, with debt covering the difference, has collapsed — leading to economic stagnation, as I explained here.

https://larrylittlefield.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/debt-and-inequality-go-together-rising-debt-is-the-cause-of-rising-inequality/

The result is a global crisis of inadequate demand, as the executive/financial class and the political/union class face the questions “who are you going to sell to” and “how can people getting poorer and poorer keep paying more taxes for less in services so you can get richer and richer?” And yet executive pay continues to rise – even though dividends paid to investors are either low or financed by debt rather than earnings.

When a company buys back shares, it can mitigate the dilution caused by the issuance of stock for executive awards according to Marketwatch.com. While buybacks don’t directly cause boards of directors to hand out stock to executives, they do provide plenty of ‘cover’ by limiting the dilution effect. But buybacks, at what might be near-record-high stock prices, may keep a company from deploying excess capital through expansion of its business, product development, efficiency initiatives or acquisitions that could drive sales and earnings. It might also keep the company from treating its non-executive employees fairly.

With existing organizations having been captured by self-serving cabals, the U.S. economy desperately needs some creative destruction. It needs new businesses to replace the old, and provide a better deal for consumers, workers, savers and investors. Younger generations will be poorer throughout their lives and the generations following Generation Greed will face old age with vastly diminished retirement savings and benefits. So maybe total sales can’t rise. But new firms can certainly take sales from existing firms, and investors from existing firms, by finding ways to lower costs – starting with less extravagant pay at the top.

Huge numbers of existing U.S. companies have been discredited, particularly in the financial sector, which is New York’s leading sector. Where are there replacements? Given what has happened in the Generation Greed era, the default choice – as a worker, consumer or investor – should be a recently founded organization with the founders still in charge. Not a cabal of corporate politics players who slimed their way up the greasy pole and are now seeking to get rich by shrinking a once great firm into a small one.

Notes Marketwatch.com

If you’re annoyed by the dilution of your investments or excessive CEO pay, with “excessive” being defined by you, there is action you can take besides making your say on pay vote. You can incorporate those concerns into your stock-selection process.

Lutin of the Shareholder Forum said the most important thing for individual investors to do, if they are investing directly in companies rather than just sticking with mutual funds, ETFs or index funds, is to research a number companies to find the ones that seem likely to “make real profits for 10 or 20 years.”

And it should be relatively easy to spot red flags. “Respect is an important element,” he said. “It’s also easy to see, since it’s a really basic element of any organization’s culture. If the people responsible for running a business show that they don’t respect any key constituencies — including you, as an investor — you can assume they also don’t respect others.”

One doesn’t need a lot of investible capital to make the same selections as workers and consumers. In the private sector, unlike the public sector, the serfs have choices if they are savvy enough to exercise them, and cannot be compelled to pay.