The Federal Reserve Z1 data on U.S. public and private debt was released for 2015 on March 10…

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/current/

and I downloaded it and updated my spreadsheet to see if there has been any progress in getting this country and its inhabitants out of the financial hole.

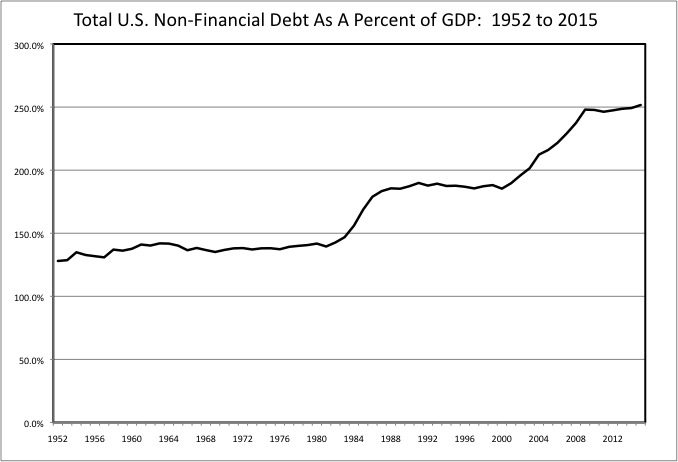

There has not. Excluding the debts financial companies owe to each other, total U.S. debts varied between 128 and 142 percent of GDP from 1952 to 1981, a time of much greater equality in the U.S. than today. But by 2008 total non-financial debts had increased to 237 percent of GDP. To the extent there has been a recovery from the Great Recession, it is because this figure increased to about 252 percent of GDP in 2015. And the U.S. economy, and the global economy, remain at the point where, in the cartoon, Wile E Coyote has run off the cliff, is hanging in the air, and realizes that gravity is about to take him down.

A spreadsheet with this data, and the charts used in this post, is here.

Total Credit Market Debt Outstanding Stat Abst

When you look at the facts, the Presidential campaign seems to be a fantasyland. Senator Clinton has decided to take the position that since the U.S. economy is slowly recovering in a cyclical sense, everything is fine. Donald Trump has identified scapegoats for people to blame for their diminished circumstances and, among those who are older, the fact that their children are worse off than they had been at the same age. Neither identifies the actual problems, nor do any of their competitors for our nation’s highest office.

The problem can be summarized this way. American businesses don’t pay most American workers enough to be able to afford the lifestyle they have sold Americans. With large, poorly-built, energy-hog houses in far-flung locations filled with lots of stuff. And long, one-person per vehicle commutes in very large vehicles. And more years spent in retirement, relative to years spent working, while taking cruises. In addition to the inflated personal costs, state and local governments can’t afford to produce and maintain all that spread out infrastructure. No problem if you are off the grid. Big problem otherwise. And federal government benefits for seniors are heading for financial disaster.

It’s a trap between falling income and rising consumption that has sprung closed, as people can’t afford to replace their cars, and are forced to retire without pensions or savings, and with debt. And with the diminishment of family and spiritual connections, many people have nothing else in their lives to provide them with a feeling of value. Meanwhile the entire U.S. economy, the entire world economy, is dependent on the unsustainable demand from Americans spending more than they have, selling off bits and pieces of the country’s future, and their own future, to pay for it.

For those who have not read my prior posts on this subject each year, allow me to once again describe the long-term trend.

Starting with the back-end of the Baby Boom, each generation of Americans has been paid less than the one before, adjusted for where they are in their lifecycle. The negative trend worked its way up the educational ladder, starting with high school dropouts after 1973, the year median wages for males peaked in this country, and moving on to high school graduates in the 1980s, after the “deindustrialization” recession early in that decade, and college graduates in the 1990s, after the early 1990s recession that was the first to really affect them. In the 1990s only those with graduate degrees were getting ahead, and by the 2000s it was just the “one percent.” But since the financial crisis only the .01 percent has been getting ahead, and perhaps soon not even them.

I’ve read a number of studies documenting this trend over the decades. Not long ago the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis released yet another such study showing the same thing, this one a highly technical multiple regression analysis that adjusts for education, whether or not one is a saver, and other demographic and social factors. It puts the start of falling income a little earlier, after those born in 1950, with the losses accelerating later.

http://www.stlouisfed.org/household-financial-stability/assets/Emmons-Noeth-Economic-and-Financial-Status-of-Older-Americans-4-Sept-2013.pdf

The Fed’s main question for this analysis was the economic status of older Americans, and indeed since the young have other advantages the diminished status of younger generations will really hit home when they become old themselves. The diminished income and wealth of younger cohorts (based on birth year) at each point in the lifecycle is summarized starting on the bottom of page 26 and shown graphically in figures 29 and 30 on pages 73 and 74. The compensation of younger generations, according to this source, was more than 20 percent lower than those who came before had been at the same age.

The Federal Reserve adjusted for education, and since the early Baby Boomers were so much more likely to go to college than prior generations, their income continued to rise in an absolute sense. Until the back end of the Baby Boom and the generations after, when higher education gradually ceased to insulate people from falling incomes. I discussed an additional analysis from the Census Bureau, comparing the well being of those ages 18 to 34 in 1980 with those ages 18 to 34 in 2010, in this post.

Falling Wages: It’s Not Just the “Millennials” and It’s Not Just the Business Cycle

During the period from 1980 to 2008 there was a seemingly sensible retort to statistics like these. The data may say Americans are getting poorer, generation-by-generation, but they aren’t living that way. Look at how many own homes, and how big those homes are, how many cars they have, and how big they are, how many have flown on airplanes to vacations far from home. Look at the luxury dorms on campus, the I-phones and Starbucks, the entitled teens and twenty-somethings and their party lifestyle, as presented in the media.

Some of this increase in consumption was only real for some people, and some of it was only on TV. But there is some truth to some forms of consumption increasing in general. It is true that people in housing projects now have color TVs and information technology, the only part of the economy with extensive investment over the past 30 years, has transformed American life. Other than that, however, in reality most Americans could not afford their more expensive lifestyles, even among those who actually had them.

Falling income per worker was at first offset by having more workers in the family, with women entering the paid labor force in larger numbers. One-parent households were certainly poor, but married couples continued to have more income and spend more money, at least for a while. Then private sector employers took away deferred income in retirement, in the form of pensions and retiree health care. The workers should have cut their spending drastically back then, to save enough to offset this, but they did not, deferring the decline in their living standards until retirement. A retirement that during the Great Recession was often earlier than expected and involuntary.

In the final phase, starting in 2000, people offset their falling incomes by going deeper and deeper into debt, until it all came crashing down in 2008. Suddenly the falling average compensation of the post-1973 period showed up in a drastically diminished standard of living for millions of people. Some of whom are young people starting out, living in less space on less income than people their age had in the past. Some of who are approaching retirement deep in debt, with no retirement savings, and often after having lost their homes to foreclosure. This diminishment is worse in the middle of the country than in a few prospering metro areas on the coasts…

http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21694356-inequality-between-states-has-risen-most-past-15-years-americas-most-successful-cities

As the most ambitious and advantaged flee the economic disaster elsewhere. It has even come to affect the age at which people die, due in large part to an increase in suicide and substance abuse.

Death is the Ultimate Statistic II: The Most Important News In Ten Years

In global and historical terms Americans are not poor, but a huge share of the population is poorer than it once was, and poorer than prior generations were at the same age. And poorer in social and family connections as well. For millions, sad times continue with no end in sight. They can only afford a standard of living that would have been a glass half full for those living in the U.S. 50 years ago, and those living in much of the world today, but is a glass half empty for those who once had, and feel entitled to, more. The glass is half full if the level is rising, but half empty if it is going down.

So much for the history.

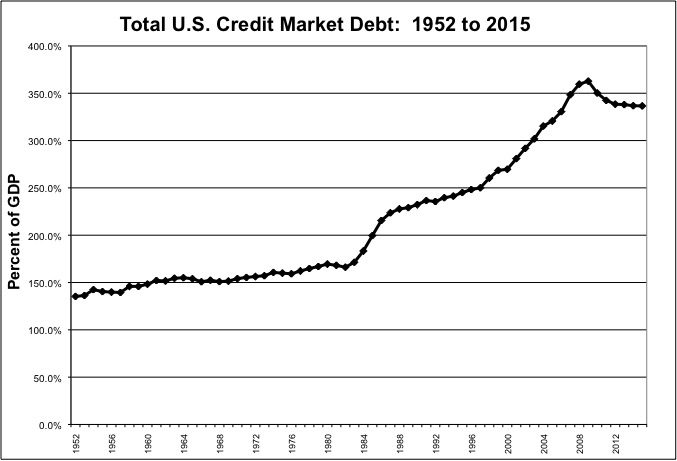

Since 2008 total U.S. debts, including public and private debts, have fallen, but they haven’t fallen much compared with how much they soared from the early 1980s to 2008.

As noted previously, if you exclude financial sector debt, the debt that financial institutions owe to each other, U.S. debts have not fallen at all. All the economic pain of the past seven years has resulted not from paying down our debts, but from merely ceasing to increase them as quickly.

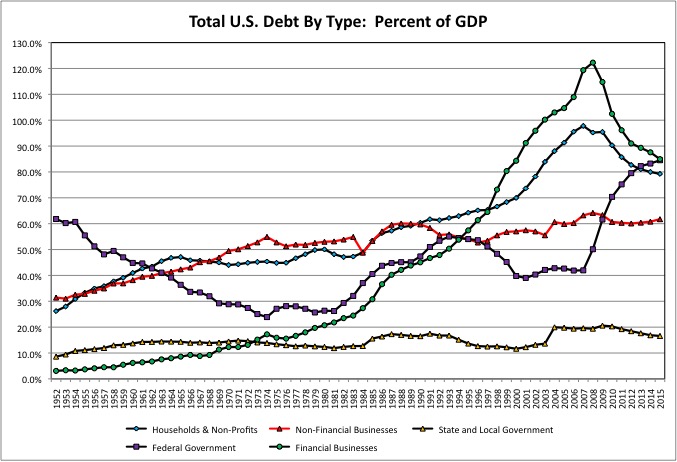

Financial debts soared as financial companies were allowed to leverage up to inflate their short-term profits, but putting at risk of bankruptcy or in need of a bailout in anything went wrong. Thus to many what happened in 2008 and 2009 was a financial crisis, but I see it as just a symptom of broader problems. And as the financial sector has deleveraged, those broader problems have remained.

With the entire world in an economic crisis of demand, due to too much spending power from actual income in too few hands, the only reason we avoided a Great Depression is that non-financial debts were kept inflated. And the only reason we have had a recovery is that total U.S. debt started rising again. Total non-financial U.S. debts were 2.4% higher as a share of GDP in 2015 than in 2014. Such debt increased from the year before, as a percent of GDP, each year starting in 2012.

The U.S. can’t keep going deeper and deeper in debt forever, but no one has any other ideas for economic recovery anymore. The initial idea of increasing debt in a recession, as described by economists, was “priming the pump.” Rising debt temporarily allowed people to spend more than they were paid, but that spending would in theory lead to more hiring, and thus rising income. Eventually that rising income would catch up with the debt and bring it back down, making the economy sustainable. But over the past 35 years the level of total non-financial debt has been at break even as share of GDP at best, punctuated by big increases.

Over the long term, debt should never have been used for consumption at all. It should have been used for investment.

With businesses borrowing to invest in plant, equipment, training, and research and development to create assets that would provide more than enough ongoing income to pay off the debt.

Students borrowing money for college only to the extent that the resulting knowledge and credentials would allow far more of an increase in income than paying the interest on the debt would absorb.

And households borrowing to purchase consumer durables such as homes, autos and washers and dryers only to the extent that doing so allowed them to save money, over the long run, compared with the cost of rent, mass transit, and trips the coin operated public laundry.

Back in the day, in fact, if one wanted to take out a second mortgage, the bank would want to know what the money was for, and would only lend if it could be described as investment and not just short term spending. Borrowing money to take a vacation, or go to Applebee’s, was not what anyone did.

One person’s debt is another person’s paper asset. Those paper assets are claims on someone’s, or everyone’s, future income, and the wealthiest have piled up huge dollar values of them. So have people in other countries, as the U.S. has run a trade deficit year-after year.

At one time paper assets, stock and bonds, were backed by real income producing assets. Today, however, most of them are backed only by promises from most Americans, individually and collectively, to live poorer in the future (now the present) in exchange for having been allowed to live richer in the present (now the past). The already extravagant (in the early 1990s) but then retroactively enriched pensions of public employees, and federal retirement benefits, are similarly backed primarily by promises to make younger generations poorer in the future than today’s retirees had been at the same age, by making them pay more in tax.

Basically, rising debts have allowed and created the big increase in inequality over the past 35 years, as I described here.

Debt and Inequality Go Together: Rising Debt Is the Cause of Rising Inequality

By providing those at the top with an answer to this question: “if most people are being paid less, who are you going to sell to?” “People who use credit cards, and take out additional mortgage debt against their home equity, that’s who.” We don’t have a trade problem, or an automation problem. We have a debt problem.

Once it became clear that people had been borrowing more than they could pay back, and that trend ended, the economy would have collapsed had not the federal government stepped in and borrowed for them. Basically allowing today’s Americans to continue to spend money now by promising the holders of paper assets a rising share of the income generated by the future work of their children and grandchildren – in taxes they will have no choice but to pay.

Had the federal government not stepped in the value of those paper assets would have been wiped out in a bonfire of bankruptcy, as in the 1930s. Soaring federal debts have been accompanied by demands for rising taxes, but not on the retired, and reductions in future federal Social Security and Medicare benefits, but only for future beneficiaries, not for the retired or close to retirement.

Despite an economy that has been expanding for half a decade, with the labor market approaching full employment, and despite tax increases and discretionary spending cuts, federal debt increased by another 1.3% of GDP from 2014 to 2015. As private debts have gone down, federal debts have gone up to keep spending going and postpone, but not solve, the global crisis of demand.

Non-financial business debt is also rising again, but not because businesses are borrowing money to invest in real, income producing assets. They are borrowing money to buy back stock and pay dividends, temporarily inflating stock prices. And thus maintaining the inflated level of executive pay that took hold in the 1990s, while diminishing the future prospects of a large set of U.S. companies. And to pay for mergers, which are reducing competition, job growth, and economic vitality. Here is one example of a once-successful New York City company.

http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20160219/BLOGS02/160219864/fairway-market-is-on-the-brink-of-default-heres-what-went-wrong

Fairway supermarket expanded too quickly and faced new competitors. But the main problem was the financial engineering of a house of cards – owners who borrowed money to pay themselves richly, leaving the company on the brink of bankruptcy and investors and lenders facing big losses.

“Back in 2007, Fairway’s founding Glickberg family sold the business to private equity firm Sterling Investment Partners for $150 million. After the transaction, the new owners had Fairway borrow heavily to fund expansion. Yet Sterling had no experience in supermarkets, where profits at even the best-run companies are measured in pennies on the dollar. Howard Glickberg, the last of the founding family to work at Fairway, left in 2014 and there was lots of management turnover. Sterling made out just fine. It pocketed more than half the proceeds from 2013’s IPO and between dividend payments, management fees, management-termination fees and stock sales, Sterling has recouped all the cash it used to buy Fairway and then some.”

Note to those reading – think twice before working for a company where the founders are no longer in charge. Unfortunately, however, the economy is increasingly dominated by existing large firms that are being pillaged by those who now control them, as entrepreneurship has decreased.

The American and New York Economy: Stagnation and Oligarchy or Renewal and Entrepreneurship?

Non-financial business debt has increased as a percent of GDP each year since 2012, another aspect of our so-called recovery that has helped to inflate yet another stock bubble. Those looking at our economic realities with open eyes, however, acknowledge that those inflated stock prices will be supported by falling income, as companies have collectively reached “peak profits.”

http://www.researchaffiliates.com/Our%20Ideas/Insights/Fundamentals/Pages/479_Peak_Profits.aspx?_cldee=aGV3ZXNtYWlsQGhld2VzY29tbS5jb20%3d

“For nearly a quarter-century, we have experienced profits growing at a faster clip than GDP. Extrapolating this trend into the future is speculative at best. Equilibrium real growth in earnings per share cannot exceed real growth in per capita GDP, real growth in wages, and real productivity growth, on a long-term basis, without violating our sense of social fairness: More rapid growth in profits than GDP means a rising share of income to capital. Capital’s share cannot rise in perpetuity; social and political forces, if not economic developments, will cause it—sooner or later—to revert to a more usual level.”

“The inflation of our profits bubble has been facilitated in part by a corporate capture of government policy, inhibiting competition, depressing investment, and promoting rent seeking. Rent seeking may be more extreme within our very own financial industry than in any other. TARP and QE are just the most recent and largest examples of government intervention to benefit corporate interests. For several decades, under governments led by both parties, the close nexus between Wall Street and Washington has facilitated an economic policy that favors politically savvy corporations and too-big-to-fail megabanks. Our policymakers have too often mistaken what is in the best interest of their elite peer group (and, surely by sheer coincidence, some of their largest campaign contributors) as in the best interest of the broader society. The result has been decades of stagnation in wages, high taxes on labor income, subsidies for debt and consumption, underinvestment, and soaring corporate profits.”

And, I have noted, all this was only made possible by soaring public and consumer debt. It could not have occurred otherwise, because there would have been no one to sell to.

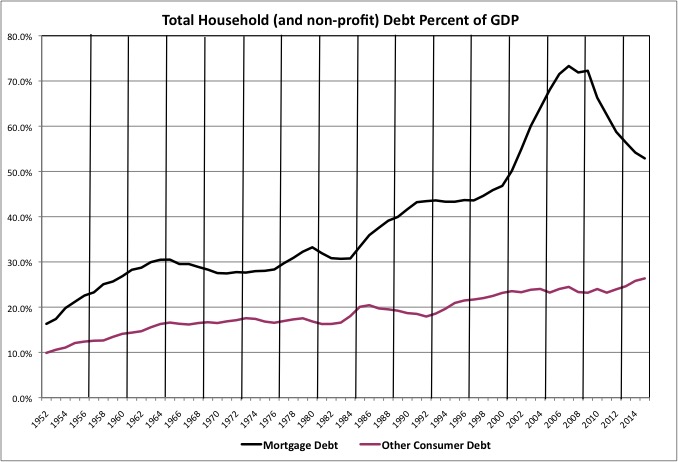

And what about that consumer debt? Total consumer debt has been going down, but only because people have been defaulting on their mortgages and ending up renting. As a result rents are rising, pushing down living standards even more.

Prior to the mid-1980s, borrowing against one’s home for a reason other than buying it was rare. Some people borrowed against their homes to get money to start a business, and others to pay for their children’s college education, but for most the goal was to pay the mortgage off by late middle age and then live rent-free for the rest of their lives. It was customary, in fact, to host a party when the house was paid for, and ceremonially burn the mortgage documents.

And prior to the tax reform of 1986, the interest on all consumer debt was tax deductable. Credit card debt, auto loan debt, student loan debt, installment debt for consumer durables. The 1986 tax reform, and increases in tax-exempt savings vehicles such as IRAs, 401Ks, and 529, were intended to discourage people from spending more than they had, and encourage savings and investment instead.

But the opposite happened, showing that culture mattered more than those economic incentives. Mortgage debt remained tax deductible, and the financial sector started allowing people to borrow against their homes for more and more things. Culminating the white-collar riot of the 2000s, with widespread fraud by borrowers, lenders, bond underwriters, bond rates, and property appraisers. This has been followed by a widespread foreclosure disaster. Foreclosures and write-offs, not paying off mortgages, are responsible for most of the decrease in mortgage debt as a percent of GDP.

It is no surprise that those places that had a high percentage of renters, and a high percentage of people using mass transit, have had a more vibrant consumer economy in the years since. In addition to attracting the best off among the younger generation, they have less of an overhang of mortgage and auto loan debt draining off consumer spending. For the rest of the country, consumer spending is only holding its own because other, non-mortgage types of consumer debt are once again rising as a share of GDP.

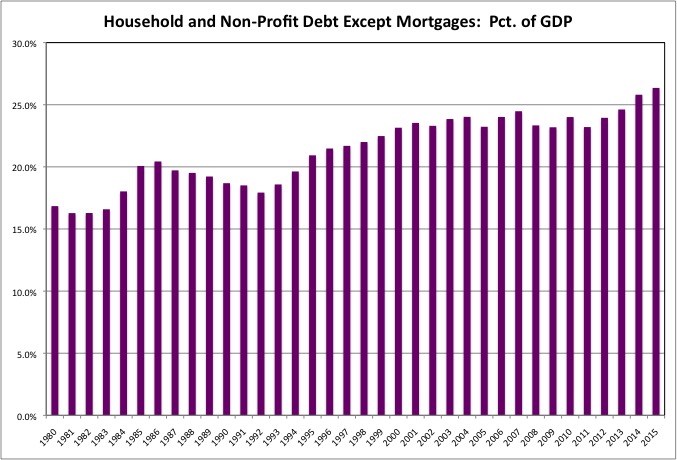

By 0.5% of GDP in 2015, and 3.2% of GDP since 2011. That, and rising federal debt as a percent of GDP, has been your economic recovery. And by the way, does anybody else get the impression that rising consumer debt – people having more to spend than they are being paid — has had a strong correlation over the years with the percent of Americans who say the President has been doing a good job?

http://www.gallup.com/poll/124922/Presidential-Job-Approval-Center.aspx?g_source=POLITICS&g_medium=topic&g_campaign=tiles

Part of non-mortgage consumer debt is auto loans. When the financial crisis hit, many Americans found they did not have the income to replace their motor vehicles as they aged. Auto demand collapsed, and Chrysler and GM had to be bailed out. Demand has since rebounded, but only because of auto lending that left consumers deeper in debt for a longer period of time, a trend only partially offset by longer vehicle lives.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-23/more-subprime-borrowers-are-falling-behind-on-their-auto-loans

“More borrowers with spotty credit are failing to make their monthly car payments on time, a troubling sign for investors who’ve snapped up billions of dollars of securities backed by risky auto debt. Delinquencies on subprime auto loans packaged into bonds rose in January to 4.7%, a level not seen since 2010, according to data from Wells Fargo & Co.”

“The data is worth watching closely, he added, ‘especially against the backdrop of subpar economic growth.’”

That growth would have been much more sub-par, particularly in the Rust Belt, if lower underwriting standards, with longer loan times to allow lower monthly payments, did not allow auto purchases by the former middle class to rebound as much as it has. Meanwhile, people continue to cling to their lifestyles in the face of falling income by running up their credit card balances.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-09/americans-can-t-help-themselves-from-borrowing-more-on-credit-cards

“Credit cards are an addiction that most Americans never shake. Through the booms, busts, and recessions of the last 15 years, U.S. credit habits have been remarkably consistent, according to a recent study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Most people carry over a balance from month to month, the study said, and they eagerly gobble up any additional credit their card-issuers offer.”

“Americans borrow more in good times and less during recessions. The driving factor isn’t our mood about the economy. Borrowing seems driven by our credit limits. When banks offer us a higher limit, we use it. When they cut us off, we tighten our belts.”

Forget “consumer confidence.” What matters is consumer capacity. And in the face of stagnant income, or worse, that capacity is the ability to go deeper into debt.

“Credit limits have the biggest effects on people who carry debt forward from month to month. When offered a 10 percent increase in credit limits, these ‘revolvers’ subsequently increase their debt by 9.99 percent, the study finds. In other words, revolvers—the majority of U.S. consumers—typically use almost every extra cent offered by their credit card issuers.”

“This is a striking statistic, but it’s hard to know what conclusion to draw from it. Are most people just incapable of resisting temptation? Or are they in such desperate economic straits that they need more credit to get by? It may be a combination of the two.”

The Catholic system of morality assumes that people have free will. Neo-classical economic theory assumes that people make rational economic decisions, taking their future needs into account as well as their present wants. But recent economic history implies that most people don’t have free will after all, and don’t make rational decisions. Or that at least that they choose to put free will and rationality aside and behave more like amoebas, single-celled organism, responding to stimuli without the benefit of a brain, let alone the presence of a soul.

In fact this thoroughly depressing book replaces the economic determinism of “scientific” Marxism with the biological determinism of sub-conscious urges when analyzing consumer behavior and the direction of society,

http://www.amazon.com/Cool-Brains-Hidden-Drives-Economy/dp/0374129185

“We live in a world of conspicuous consumption, where the clothes we wear, the cars we drive, and the food we eat lead double lives: they don’t merely satisfy our needs; they also communicate our values, identities, and aspirations…Quartz and Asp bring together groundbreaking findings in neuroscience, economics, and evolutionary biology to present a new understanding of why we consume and how our concepts of what is ‘cool’-be it designer jeans, smartphones, or craft beer-help drive the global economy. The authors highlight the underlying neurological and cultural processes that contribute to our often unconscious decision making.”

“Through a novel combination of cultural and economic history and in-depth studies of the brain, ‘Cool’ puts forth a provocative theory of consumerism that reveals the crucial missing links in an understanding of our spending habits: our brain’s status-seeking ‘social calculator’ and an instinct to rebel that fuels our dislike of being subordinated by others. Quartz and Asp show how these ancient motivations make us natural-born consumers and how they sparked the emergence of ‘cool consumption’ in the middle of the twentieth century, creating new lifestyle choices and routes to happiness.”

This is debt-funded shopping. This is your brain on debt-funded shopping.

If the authors are right less ability to spend, with lower incomes now joined by maxed out credit, thus means less happiness.

While I don’t want to accept it, the two leading candidates for President (at present) certainly see people as sheep to be manipulated. For Senator Clinton this is an obstacle to be overcome. She can’t be straight with people, things she has said over the years seem to imply, since they don’t know what is really good for them. For Donald Trump the desperate pursuit of social status and sexual contest is a business opportunity, and as nauseated as I am I can’t help but admire the brilliant way he exploits it.

At one time credit card interest rates were capped by usury laws, and card issuers were thus prevented from making enough profits on those who paid to cover defaults by those who got in over their heads. And bankruptcy laws made it easy for people to walk away from high credit card debts. The banks, therefore, were discouraged from lending people more than they could pay back without impoverishing themselves. But then competition among states for credit card processing jobs, starting with North Dakota, caused those usury laws to be wiped away.

http://www.creditcards.com/credit-card-news/marquette-interest-rate-usury-laws-credit-cards-1282.php

And the bankruptcy reform law of 2005, conveniently passed right as total consumer debt (including mortgages) was peaking, ensured that people could be permanently impoverished in the future after having “lived richly” in the past.

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/08/opinion/the-debtpeonage-society.html

Those who pushed that bill through certainly knew what was coming.

Lending people more than they can pay back without impoverishing themselves is one part of what I call the “just enough rope to hang themselves economy.”

This includes the ubiquity of gambling, after state and local governments turned to casinos en mass in the 2000s to revive their economies and bail out their budgets. Today there are so many casinos that a large number, including those once owned by Donald Trump, have gone bust. How much of that government-promoted increase in gambling was financed by home equity lines of credit and credit card debt?

Today the great hopes seem to be artisanal alcohol, medical and non-medical marijuana, ubiquitous porn, and the Roman Coliseum-like thrill of Mixed Marshall Arts. Where one can now experience the thrill of two young women who wearing little beating the hell of out each other in a cage, with perhaps the prospect of one of them being killed in the ring eventually. And, while this has not yet been legalized for the tax revenues, all the heroin you can inject.

At one time our society felt an obligation to at least try to protect the ignorant, the short-sighted, the depressed, the easily manipulated, and desperate people with few options, from themselves. Some of this still goes on with of dissipating momentum – the backlash against head injuries in football, for example.

For the most part, however, we now have an economy in which those out for a buck have the right to solicit the vulnerable to do things in the present that damage their future, on the grounds that if they take the deal then they get what they deserve. Instead of accepting that they deserve it, however, those who realize the consequences when the future arrive seem to prefer to vote for Presidential candidates that offer them scapegoats as a substitute for self-loathing. Scapegoats on which to vent their anger.

Far from being concerned about the effect of all this on society, there seems to be greater concern that the younger generation is not following the same pattern.

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/why-boomers-are-loading-up-on-debt-and-millennials-arent-2016-02-12?link=MW_home_latest_news

“A new report from the New York Federal Reserve shows older Americans have been ramping up their debt while younger Americans have not. In real terms, debt in the hands of Americans between 50 and 80 years of age has increased by 59% since 2003. At the same time, the aggregate debt of those age 39 has dropped by 12%.”

The problem is that younger generations are not permanently impoverishing themselves by borrowing money to buy older generations’ houses at prices inflated enough to cover all that mortgage debt.

“Home-secured debt, per capita, has surged 47% for those age 65, for an increase of $11,191, while it’s dropped 28% to $8,195 for those aged 30.”

Over age 65 with a mortgage? Back in the day the bank made my father take out a 15-year mortgage, rather than a 30 year mortgage, because it didn’t’ want him to still be in debt past 55. How do older generations expect younger generations, who are paid less, to pay them high prices for their houses and stocks? With what money? No wonder there has been such an emphasis on marketing to overseas buyers in recent years, though that too seems to have run its course.

“That same trend played out for auto loans as well — on a per-capita basis, auto debt is up 29% for those 65 years old, but it’s down 6% for those 30 years old.”

Younger generations are flocking to places where they can save the cost of a car by using mass transit. But mass transit is collapsing as a result of the state and local government debts, under-funded and retroactively enriched pensions, and inadequate infrastructure investment run up by the generations before them.

Sold Out Futures: A State By State Ranking Based on the Census of Governments

“Student debt is for the first time becoming an issue at age 65, surging 886% (though it’s still rare.) Meanwhile, 30-year-olds have seen a 174% increase in student debt per capita.”

As state funding for public universities have been reduced and costs at private universities have soared. So what is the big concern?

“The report notes that the more muted borrowing of younger consumers has consequences, in particular as they are less able to get on the housing ladder and build wealth.”

Actually the young have other concerns, which they express to personal finance advice columnists.

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/will-my-husband-and-i-be-saddled-with-his-parents-200000-debt-2016-03-04

“I have a question regarding the debt of my in-laws after they pass away. My husband and I have lived away from home since age 19 (we are now in our 30s). We have put ourselves through college, forgoing a formal wedding ceremony or honeymoon to instead pay down student loans. We own our own home and have children. We do not have much extra money at the end of the month but are still financially stable.”

“My in-laws… are racking up huge amounts of debt. Last I heard it is up in the $200,000 range in credit-card debt alone. Their house is not paid off and my father in-law is disabled. I refuse to pay for my sister in-law’s luxurious lifestyle, but I am afraid after my in-laws pass we will be the only family with the financial capability to pay it off. In the event of them passing who will be responsible for their debt? Is there a way to protect my husband and I from being stuck with the bill?”

“To answer your question: No, sons and daughters are not liable for their parents’ debts when they die.”

Not yet as individuals. But after the next bankruptcy reform law, passed out of desperation to get consumer spending up again by loosening credit and encouraging borrowing and lending, who knows? And how about the collective credit card debt, the one on the books of the federal government?

Yes the economy is in a cyclical upturn – thanks to debts once again rising as a share of GDP. But how can anyone look at the long-term trend in average income and total debt and think things are fine? How can anyone see that increase in the death rate and be shocked? How can one not conclude that the 2008 financial crisis was not merely the start of a normal recession but rather than collapse of an unsustainable economic era, or what would have been the collapse had not the federal government kicked the can?

Are things are fine for people like me, households with two people with graduate degrees, no debts, and a house in New York City purchased in between housing bubbles? Sure. Fine for most Americans, years after the Great Recession officially ended, and for younger generations? Absolutely not.

Saying things are fine is, among other things, a political loser. Not that I know what the government could, or should, do in the face of this social tsunami, but it is foolish to pretend that people aren’t drowning.

This is not a future of Trump Steaks and lots of goodies being handed out, the bill passed to someone else sometime else. That economy is dead. It is about making adjustments, learning to live on diminished incomes, and learning to make money based on what your customers can actually afford to pay. Many young people seem to get that, and are trying to find their way.

Many of those who took us down this path, however, still do not get it. In this context, and given this reality, the continued demands of those who piled up promises to themselves in the past 35 years are simply intolerable.